Blink and you’ll miss it. Eisenheim the Illusionist has asked you to place your handkerchief in the ordinary wooden box he’s provided for you, and though you are sure you are concentrating on it… it has disappeared. Never fear, for the magician, like any good showman, will have you kerchief reappear while you are distracted watching an orange tree sprout from seedling to fruit-bearing tree in a matter of seconds.

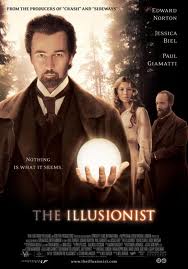

Much like the master magician’s trick, is Neil Burger’s 2006 film, The Illusionist. Though generally well-received, it was soon overshadowed by Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige only a month and a half it’s US premiere. But now, perhaps is the exact right moment for The Illusionist to step out from behind the curtain and dazzle the audience once again.

Both films center around a turn-of-the-twentieth century magicians, and both are adaptations of literature. But simply because Edward Norton, Jessica Biel and Paul Giamatti finished second in box office revenues and general hype to Hugh Jackman, Christian Bale, Michael Caine and Scarlett Johansson, doesn’t mean the film should settle for the silver medal forever.

Without taking a stance on which was the better film, each should be allowed to stand on it’s own merits. For The Illusionist, its greatest strengths are its stunning visuals, passionate score and talented supporting cast. Though there is a darkness to the magic, the overall aesthetic of the scenes and the decadence of Vienna counteracts any overbearing heaviness.

The Illusionist, based on Steven Millhauser’s short story, “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” in his short story collection, The Barnum Museum, begins in media res as Eduard Abromovich (Eisenheim, played by Norton) sits on a bare stage in a simple wooden chair, sweat beading at his hairline as he stares intently at what appears to be empty space in the foreground. From that first tension-filled moment, the story moves from present time to Eisenheim’s childhood up through the present as Chief Inspector Walter Uhl (Giamatti) recounts the events to Crowned Prince Leopold (Rufus Sewell).

Norton’s portrayal of the enigmatic illusionist leaves enough room to allow for the strong performances of the rest of his cast to dominate the story line, though in doing so does not diminish the power of his own performance. Though Inspector Uhl is able to retell many of the events that shaped the magician’s early years, the audience knows little of current personal life. He orchestrates the events of the story as he orchestrates his illusions. Norton takes on the role and becomes the quiet driving force in order to be the the pacifist whose actions spark aggression and passion in others.

In the crowned prince, he sparks much anger and frustration after Leopold learns that Eisenheim and his soon-to-be-fiancee Duchess von Teschan (Biel) share a history. Sewell is every part the jealous man, excellent at portraying a character the audience has no qualms about hating from the beginning. At a dinner party for which he invites Eisenheim to provide entertainment, his firm command of the room asserts his dominance and solidifies his insecurities about his place in the empire at the same time. His foreboding warning to Eisenheim—don’t embarrass the crowned prince in front of his guests.

And Biel’s turn as the beautifully delicate yet determined duchess retains the purity of youth even as she schemes behind her suitor’s back. She explains her situation to Eisenheim saying, “it’s a game I have to play.” The scenes of her childhood romance with Eisenheim inform much of her actions throughout her very public adult life. In many ways, Biel’s character has not grown out of her childhood, and this is evident in every glance and gesture. The love and history the two share is so innocent and childlike, it’s no wonder she was his first and only love. But there is another side to her, one Biel gracefully brings to the surface. The duchess is a woman who knows what she wants once she has found it and would even be willing to die for it.

Giamatti also delivers a noteworthy performance as the inspector. As a man torn between political loyalty for the sake of his career and his curiosity and personal interest, Giamatti not only verbally narrates the story, but illustrates much of the unspoken plot with his eyes. Standing in the train station, trying to piece together the investigation, his eyes dart frantically around, not only trying to find the illusive Eisenheim but to also figure out where the illusion ends and the truth begins. He is a hardworking butcher’s son with an eye towards furthering his career through his connection to the crowned prince, and Giamatti balances both sides quite well.

Not only are the characters brought from script to screen masterfully, but the care in transcribing them from page to script is equally matched. Though Millhauser’s story brings all these characters to life, Burger maintains their original allure even while undertaking the daunting task of turning a short story into a full-length feature film. Many of the scenes seemed ripped straight out of the book, especially with regards to the childhood sequences and the illusions. Including much of the intricate details from the story, keeps the storytelling vivid and engaging. Though much of Eisenheim’s adult life has been changed to accommodate of the length of the story, the changes are easily forgiven and could even be seen as improvements on the original. For example, though Millhauser chooses to explain away a majority of the secrets behind the illusions, the lack of explanation in the film furthers the mystery.

All of these performances are set against the backdrop of a decadent Vienna, though much of the movie was actually filmed in the Czech Republic. From the duchess’s lavish period costumes of layered skirts and white billowy blouses to the rich wooden bookshelves lining Leopold’s office, every detail stands in clean, sharp contrast. Even Eisenheim’s illusions reflect the opulence of the city. In one, an orange tree grows from an ornate bucket, blossoming and budding into real oranges and at last two butterflies of a beautiful shade of blue emerge from within the tree.

Color plays an important role throughout the film. The sepia tones which pervade the entire film and the zeroing-in effect at the close of certain scenes give the audience the sense that they are watching a movie from the turn of the century (although we, of course, now have sound). Scenes from Eisenheim’s childhood are cast even deeper in muted tones and black-edged frames to keep them separate from the recent past, which are, in turn, kept separate from the true present when Uhl confers with Leopold. The muted colors allow for certain details to stand out—the blood red of the magician’s cloak, the deep green of the emeralds on Leopold’s sword.

And the score from Philip Glass is yet another element of the film that blends so seamlessly into the background yet remains a powerful driving force, heightening tensions, playing up the past and impassioning every scene. Even the wide city street shots have the added emphasis of dramatic melodies which add the right amount of emotion without overwhelming the shot. And the music used in the flashbacks—whether childhood reminiscences or explanatory sequences—match in feeling.

As the film’s tagline states, “things are not as they appear.” The duchess’s carriage ride with Eisenheim was not a romantic rendezvous but a revisitation of childhood, and that’s not a commoner sitting in the eleventh row, sixth seat, it’s the crowned prince in disguise. Magic and mystery underscore every action of the plot from the obvious mirror illusion on stage to Eisenheim’s secret workshop filled with all his gadgets and tricks. And even though the audience knows these things to be tricks of the camera and the computer which have logical explanations behind them, the magic still holds, much more so than the magic nearly fully explained in “The Prestige.”

Though the film seems to draw to a conclusion in Leopold’s office with Uhl, the true final scene provides the right amount of closure. It’s as if the film is the story of Eisenheim’s greatest illusion, and his gift to us is a peak behind the curtain. All the thematic elements add up to a seemingly impossibility, but as Inspector Uhl tells Leopold, “Perhaps there’s truth in this illusion.”