As Americans, we tend to distance ourselves from the violence of war. It’s not happening in our neighborhoods–military aircraft aren’t flying over our heads and soldiers aren’t patrolling our streets with their AK-47s. It’s someone else’s war. But director Paul Greengrass’s Green Zone forces the audience into the middle of the action, making it our war. Only problem is, once you’re in it, there’s no escape, as much as you may want one.

Based on the book Imperial Life in the Emerald City by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, a Washington Post journalist, the film follows Chief Warrant Officer Roy Miller’s (Matt Damon) crew on their search for weapons of mass destruction following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq. But when intel proves faulty at three different confirmed WMD sites, Miller sets out to investigate the reliability of the reports and is caught up in a bureaucratic tangle of secret sources and hidden agendas.

The two opposing sides are lead by Pentagon official Clark Poundstone (Greg Kinner) and CIA Baghdad Bureau Chief Martin Brown (Brandon Gleeson). Brown allies with Miller in his search for answers, saying of the Poundstone and the opposition, “All they’re interested in is finding something they can hold up on CNN.” Miller also encounters Wall Street Journal reporter Lawrie Dayne (Amy Ryan) as the two straddle both sides in their attempt to devise the truth about the government’s reasons for going to war.

The obvious hang up of this film for many movie goers is its political nature. The events of the film are based on the events that took place following the US army’s invasion of Baghdad. Inevitably, for the majority of America, it will either serve as vindication for those opposed to the Iraq war or only serve to further incense those who supported the invasion. And because the melding of actual events and supposition is so seamless, it’s safe to assume that the average viewer is not going to take the time to separate the fact from fiction. In general, people will believe what they want to believe.

Even still, conservatives should be comforted somewhat by the fact that for the majority of the film, blame is cast on the ignorance of individuals and the structure of the bureaucracy. Granted including former President Bush’s infamous “Mission Accomplished” speech on a mess hall TV does seem a little condescending, but when the “jack of clubs” General Al Rawi confronts Miller saying, “Your government wanted to hear the lies,” both camps will side with him. And though the pro-Bush, pro-war side is painted as the villain, you can’t help but wonder what public opinion would have been if troops had actually found WMDs. Would that have justified unsubstantiated or even fabricated intelligence before the fact?

Politics aside, Greengrass must be credited for such a daring undertaking on a topic still relatively fresh from the headlines and one that is quite inflammatory no matter what your political leanings. He recently told Variety, “Film shouldn’t be disenfranchised from the national conversation. It is never too soon for cinema to engage with events that shape our lives.” But while the moxie and vision are there, the viewing experience and substance are not. Greengrass’s intent in using hand-held camera techniques was clearly to put the viewer in the midst of the action, but what it ends up doing is nauseating the audience with relentless chase scenes filmed helter-skelter through the streets of Baghdad and dizzying, zooming arial shots of the Green Zone. In this instance, moderation would have gone a long way in making an already hard to watch film an easier piece of cinematic fare to digest.

But there are moments of levity. A tourist couple stands at the entrance to Baghdad to pose for a picture, a Burger King sign hangs in the background of one scene and one of the guards at the detention center sits watching an Oregon-UCLA basketball game playing on TV. These snippets, much more than the intense action sequences that litter the film, are what give the film character and give the viewer several, if brief, moments to catch their breath. But only a handful of moments in an nearly two-hour movie may leave you gasping for air by the end.

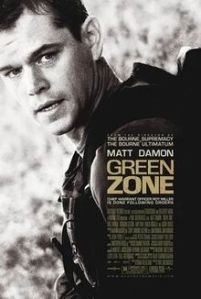

Though the film has been sold largely on the Bourne team of Greengrass and Damon, fans of the spy thriller shouldn’t expect the same caliber of film. For a film on a topic so controversial in subject matter, it does very little to separate itself cinematically. More importantly, it really doesn’t do enough to differentiate itself from other war movies until the very end, even feeling formulaic at times. America invades a foreign country, politicians are corrupt and evasive, one man takes a stand against the all-powerful government. Yes, thank you, we’ve seen it. And we know enough of filmmakers like Michael Moore to know that Hollywood leans left of center (sometimes a little too far left). The bottom line is, if you want to see a war movie, try Hurt Locker, and if you’re a Matt Damon fan, he’s much better in the Bourne films.